P/E: The Most Misunderstood Ratio in Finance

The P/E isn’t value. It’s a story.

Nature is too complex for our limited brains to fully grasp. So we cheat a little. We use models: simplified versions of reality. Not to tell “the truth,” but to make thinking possible.

George Box put it perfectly: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” Useful because they capture just enough—and stay simple enough.

The price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) ticks those boxes. It claims to get a handle on something profoundly complex—the value of a business—by using something simple on the surface: a price divided by earnings.

However, its apparent ease of use has “democratized” it in a way that has distorted its original purpose—to the point that the P/E is probably the most misunderstood ratio in finance.

Not All Earnings Are Equal

Take two companies. Both trade at a P/E of 15, have the same market cap, and posted the same EPS last year.

On paper, they look comparable. But suppose I tell you that:

Company 1 sells software, with recurring revenue, strong customer stickiness, high margins, and little CapEx.

Company 2 makes steel, with a heavy balance sheet, pronounced cyclicality, volatile margins, and a lot of CapEx.

At that point, it’s obvious that “P/E = 15” is not describing the same reality.

And that’s normal. The P/E is not a direct measure of “value.” It’s a price divided by an accounting profit per share at a point in time. And accounting profit is probably one of the most unstable objects in finance.

It depends on:

accounting standards (revenue recognition, depreciation, provisions, stock-based compensation (SBC), impairments),

capital structure/allocation (debt levels and therefore interest expense, buybacks, dilution),

management choices (provisioning policy, investment timing, capitalizing vs expensing, one-offs, deferred revenue),

and the nature of the industry (cash cycle, revenue cyclicality, capital intensity, pricing power).

A P/E only becomes interpretable once you’ve answered the question: “What kind of E is this?”

And that’s where most investors get it wrong.

Fix the E, Not the P.

A common way to use the P/E is to hold P fixed and let E float. Do that, and you can bend “reality” however you want, along with all the usual biases: cherry-picking, convenient adjustments, mixing up cyclical with durable, and so on.

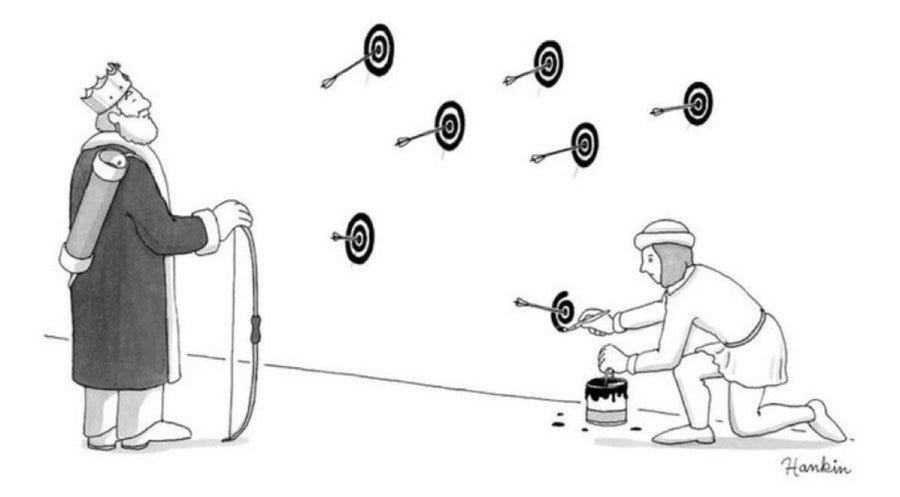

From a valuation standpoint, it’s like shooting an arrow at random… then drawing the bull’s-eye around where it landed.

The opposite approach—the relevant one—is to fix E. That pins down at least one reality, and therefore a set of implicit assumptions.

For example, if you assume +10% EPS growth per year, you’re imposing a constraint: what combinations of price/volume/margins/CapEx/dilution can actually produce that +10%? And which ones can’t?

The ratio only becomes useful at that point: once E is set, P simply tells you what the market is willing to pay for those scenarios. Then, with what you know about the company, the industry, the management team, etc., you can narrow the scenario set and refine their probabilities.

For instance, if the company is already running at full capacity, that +10% can’t come from volume. It has to come from higher prices, a better product mix, or higher margins.

The P/E Is a Price on Assumptions

The P/E isn’t a verdict. It’s a starting point—then you work backward to uncover the assumptions baked into it.

In other words: what has to be true for 15x to be rational? And if I don’t believe it, what is the ratio actually telling me?

To make that concrete, here’s the checklist I force myself to fill out every time I lean on the P/E (which is less and less often):

Which “E” is the right one, and why?

TTM / Forward / Adjusted / Normalized. Make the choice upfront, justify it, and stick to it to limit bias.What are the one or two main drivers of growth?

Price / Volume / Margins / Mix / M&A / Net buybacks. If the business analysis doesn’t give a clear answer here, it’s better not to use the P/E at all.What does that growth cost?

CapEx, working capital, R&D, promotions, SBC, etc. The answer is rarely obvious (and often a mix), but every component has to be backed by something concrete: past numbers, management guidance, explicit decisions.Does the story still work per share?

Growing total earnings at the expense of EPS is a real risk. The share count is part of the model.What would automatically invalidate my scenario?

It should almost always be a specific, binary fact tied to a timeframe. Example: operating margin doesn’t improve over the next four quarters.

After you’ve answered those questions, there’s only one thing left to do: estimate how likely the path is that would make your E true.

In other words: does your E happen under conservative assumptions (so you have a margin of safety), under ordinary ones, under heroic ones, or under assumptions that are basically impossible?

Take a simple example. You fix EPS growth at +10% per year.

If the company already has proven pricing power, recurring revenue, and doesn’t need much CapEx to grow, then +10% is a pretty ordinary (even conservative) assumption.

But if that same +10% requires volume growth, margin expansion, and CapEx funded by issuing new shares, then +10% becomes a heroic case.

Same E. Very different probability. So the acceptable price can’t be the same.

The P/E isn’t a shortcut to value. It’s a shortcut to a story. And that shortcut is only useful if you’re willing to read that story and spell out exactly what would make it true… or false.

But in the end, the P/E is still anchored to an accounting concept—earnings—that can be shaped too easily:

“Common yardsticks such as dividend yield, the ratio of price to earnings or to book value, and even growth rates have nothing to do with valuation, except to the extent they provide clues to the amount and timing of cash flows into and from the business.”

Warren Buffett — Letter to Shareholders (2000)

That’s why I tend to prefer other metrics, especially those built on enterprise value (EV) and cash flows, when assessing valuations. But I’ll save that for future posts.

Thank you for your time and attention.

Respectfully,

The Time Investor

Great write up. You're right, P/E has many flaws and is quite simplistic in many ways. Ideally, an adjusted metric should be calculated for valuation purposes - like for instance Owner's Earnings.

This was a great read. You're absolutely right about the flaws of using P/E.

It's even more dangerous when it used as a screening tool...

I like how you said P/E is a start rather than the end. An investor needs to peel back the layers to ensure what form of adjustment to make.

That said, an adjusted P/E is still good as a 4th/5th "check" (with the superior EV and Owner Earnings multiples ahead of it) to see whether a stock is cheap or expensive relative to earning power.