Brand Moats: Turning Trust Into Outsized Returns

One of the most resilient types of moat (if not the most).

This post is a collaboration with Brian Coughlin from Coughlin Capital . If you like my work, you’ll likely appreciate his as well.

Investing means making a series of decisions in an uncertain environment. A skilled investor will focus on reducing uncertainty wherever possible.

To do that, they analyze businesses in depth to estimate how much additional value a company can create over time relative to what’s already implied by its market price.

This assessment starts with the moat: the company’s ability to sustain its profitability over time, especially by earning returns on capital above those of its peers.

Here, we’ll focus on what is likely the most durable moat: brand power.

A Brand Is Much More Than a Logo

Economically, a brand is a trust premium that:

reduces the perceived risk for the customer

helps them make a decision more easily

allows the company to charge higher prices, drive more frequent purchases, and extend customer lifetimes.

This trust premium matters most in markets where product quality is hard to assess at the time of purchase, in what we call “experience goods.”

A brand does not create value by simply telling a story, but by changing how demand is structured.

For the company, this translates into higher prices, defensible volumes, and superior margins.

The existence of a brand can be observed empirically in three ways.

Loyalty

Customers come back because they actively prefer this product.

Here, the repurchase rate is high, churn is low, and most importantly, the cost to win a customer back is lower than the initial acquisition cost.

Customers know the brand, its characteristics, and sometimes even identify with it. They may also promote the brand through word of mouth, recommendations, and so on.

For the company, this loyalty translates into more predictable cash flows. In luxury and ultra-luxury, supply is deliberately capped well below potential demand. The company can almost choose its growth rate and margins while maintaining a long-term focus on brand preservation.

Stable Preference

Here, it’s less about loyalty and more about default choice. It’s the product that naturally comes to mind for the consumer at the moment of decision.

This form of brand power shows up most often in mature categories where large-scale marketing has been deployed for years, or even decades.

You see it when a brand name replaces the generic name of a product. For example, saying “a Kleenex” for a tissue or “a Post-it” for sticky notes.

In this case, even though brand effects are clearly present, the economic advantage is thinner. Competing products can often easily copy the item and make it similar enough to the reference product to “fool” the consumer.

Premium Pricing

When a brand can consistently sell at higher prices than its competitors, without relying on promotions, that’s a clear expression of brand power.

The reason can be clearly superior quality combined with higher desirability, easier access to the product, more varied use cases (network effects, ecosystem), and so on.

Here, the economic advantage is clear as long as the price premium exceeds the cost of the underlying advantage (quality, ecosystem, use cases, etc.).

These different expressions of brand strength can stack on top of each other. A concrete example is Ferrari, which is known for keeping customers loyal for life from their very first purchase, and for charging a massive premium for its cars without doing any advertising.

Here is an interesting story from Mohnish Pabrai1, who was first a Ferrari shareholder and later became a customer:

But this premium pricing is incompatible with stable preference, because Ferrari’s products are only accessible to a small minority. That’s not a problem in itself. What matters is how this brand translates into a moat for the company, and therefore into performance.

Turn a Brand Into a Moat

There are several ways to turn a brand into a moat, but the underlying objective is always the same: deliver additional value to the customer. There are, however, different types of value.

1. Selling Certainty

A brand can create a moat by reducing two invisible costs for the customer at the time of purchase: the search cost and the cost of being wrong.

In most markets, the customer doesn’t know whether the product will hold up over time, whether it will truly deliver on its promise, and so on.

A brand can build a moat when it reduces these doubts in ways that are obvious to the customer. It can do this by:

Making the promise simple, consistent, and verifiable.

Alibaba’s Tmall and its “try-before-you-buy” programs in China that let customers receive and test products at home before paying.Offering clear guarantees (after-sales service, returns, refunds, etc.).

Amazon’s almost universal 30-day, no-questions-asked return policy on most products.Standardizing the customer experience.

Anyone who sees the features of a Ferrari model knows they will get the same characteristics if they buy one.

The higher the cost of making a mistake, the more powerful this strategy becomes. This is why some sectors are inherently more prone to strong brands, due to higher intrinsic risk: healthcare, childcare, automotive, and so on.

2. Selling a Product Perceived as Different From the Competition

A Ferrari can be replicated, but it is very unlikely that Stellantis could sell a “Ferrari” at the same price as Ferrari.

What matters is how consumers perceive the product as unique and different from competitors. The customer isn’t buying a product, they’re buying this specific product.

The key word here is “subjective”: we are in the realm of perception. The brand has to play on that to build a powerful moat by:

associating the product with a desirable social status

offering a product with a distinctive, easily recognizable aesthetic

tying the product to an implicit value system

The goal here is not to make comparison easier, but to make comparison irrelevant. In these situations, price matters less and alternatives are perceived as “not for me.”

If selling certainty is about being the best at the existing game, this approach is about changing the rules of the game by reshaping the competitive landscape.

To get there, the company must choose a clear territory and deliberately give up others, accepting that it will not appeal to everyone, while repeating the same signals until they become intrinsically tied to its products.

Once the company has done this successfully, competitors may offer comparable products, but they won’t be able to capture the same demand. At that point, the moat exists.

3. Selling an Automatic Choice

Here, the goal is neither to be the best at the game nor to change the rules. The goal is simply not to play. More precisely, the objective is to turn the purchase into a habit. No comparison, no perceived risk.

The brand needs to become a cognitive shortcut. To achieve this, it must:

Make the brand instantly recognizable

Reduce friction at every touchpoint

Create continuity between past and future experiences

What matters here is consistency: stable packaging, coherent colors, distinctive visual and audio signatures. Thanks to this, the brand is recognized instantly, associated with an experience the customer already knows by heart, and this directly triggers the purchase.

The mere sensory stimulus of the product triggers the purchase.

A competitor trying to break in is not fighting a product, but habits.

4. Anchoring Brand Perception Over Time

Building a moat from a brand is only possible when the process is intentional. It requires strong, sustained managerial discipline. It doesn’t happen by accident.

The goal is to consistently sacrifice short-term gains in favor of long-term performance, guided by one principle: coherence.

The brand, its ideas, its offering, its values: all of this must remain coherent over time to anchor the customer’s perception of the brand to something desired and desirable.

This sometimes means deliberately limiting growth or refusing “opportunistic” extensions that would dilute the brand’s coherence (for example, sourcing lower-quality auto parts just to save money).

Management’s mantra should be to treat the brand as a compounding asset while staying acutely aware of its fragility. That requires impeccable discipline over time, which is not unlike the qualities of a good investor.

For some brands, it’s obvious that they are backed by a real moat. For others, even if management says it loudly and often, that’s far from guaranteed.

So you need to identify a brand moat through the numbers.

Tracking a Brand Moat

There are three main criteria to look at to confirm the existence of a brand moat.

1. Pricing Power: The Most Direct Test

This is the hardest criterion to fake. When it’s present, demand is not driven solely by price, and customers are willing to pay more because the perceived value exceeds the alternatives.

You see it in:

Price increases running ahead of inflation

Volumes that remain relatively stable over time

Limited reliance on discounts, ideally no promotions at all

An improving mix, meaning customers are trading up to higher-end products

Margins higher than the average for the non-premium / non-luxury peers

If a company shows several of these traits, it’s very likely that its brand is tied to a real moat.

The next criterion helps you confirm it.

2. Resilience in a Recession

Boom periods, with strong growth and high margins driven by operating leverage, can create the illusion of a moat.

But when growth slows or a recession hits, the absence of a moat is often exposed. In those times, consumers make trade-offs: they cut spending, spend more time comparing options, switch to cheaper alternatives, and reduce volumes.

This is when a brand moat is really tested. What matters is observing how things change and comparing that to competitors:

Margins that decline less than those of peers

Volumes that prove more resilient

And above all, the ability to hold pricing

Post-crisis performance is also interesting to watch. Historically, brands with a moat tend to recover faster after shocks than competitors without strong brands.

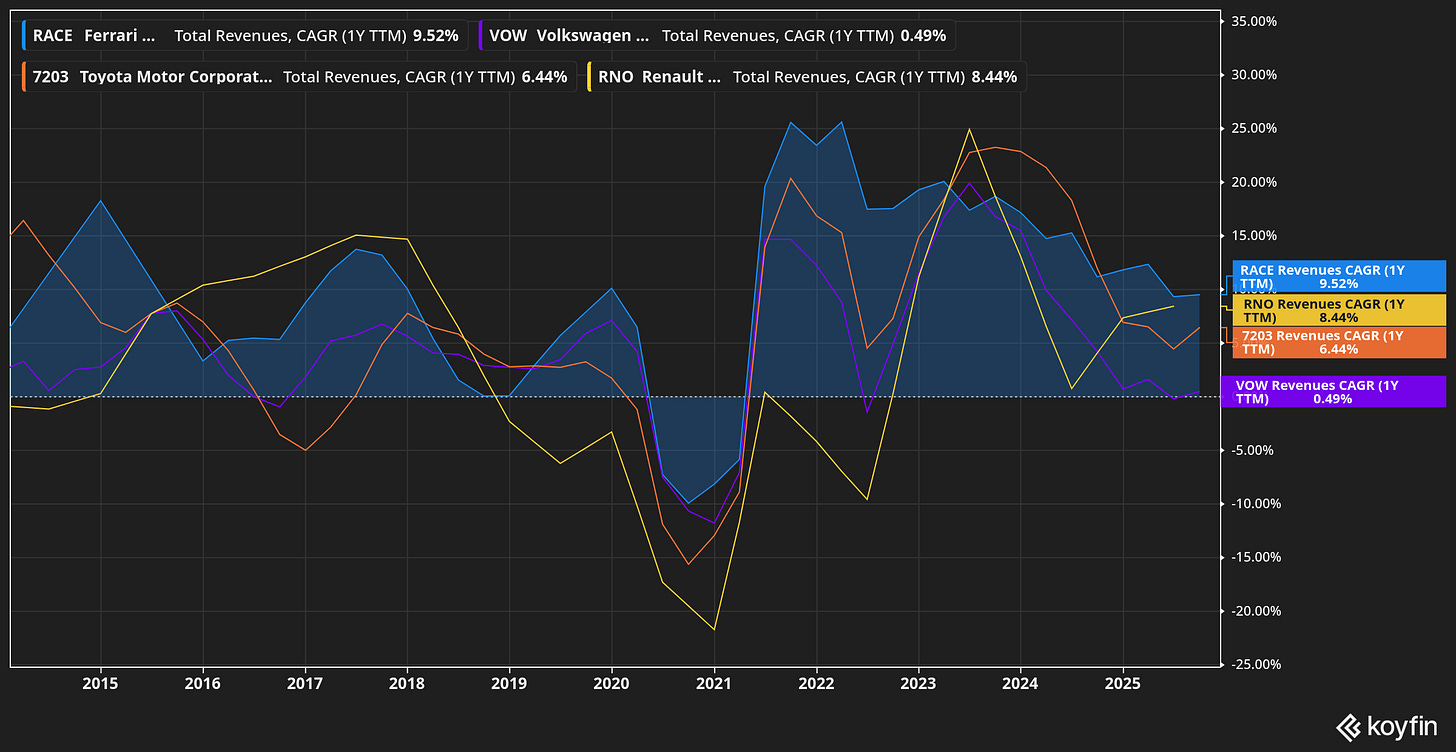

Ferrari is again a good example. When you compare Ferrari’s revenue growth to that of the largest car manufacturers, you can clearly see this pattern: a smaller drop during downturns and a stronger rebound afterward.

3. The “Quality” Share of the Market

Given the relatively high price/volume profile of branded products, what matters is not total market share, but the share of the “quality” segment of the market (premium, premium+, luxury, etc.).

Chasing overall market share by cutting prices or moving down into the entry-level segment is often destructive to a brand moat. That’s a volume game, and volume isn’t the key variable for a strong brand.

Beyond volume, a brand moat allows a company to gain market share, and therefore revenue growth, by moving upmarket.

What really matters are the average selling price and the brand’s ability to get customers to “accept” more expensive versions of the product. That allows the company to extract more value per customer while maintaining, or even improving, the brand’s perception in the eyes of the public.

In the end, a brand-based moat is one of the most durable. It is relatively insulated from technological disruption, less exposed to direct competition than other types of products, and requires relatively little incremental investment to maintain.

A strong brand moat increases the odds that a company can reinvest a significant share of its earnings at attractive ROICs, without needing heavy reinvestment just to sustain growth, and do so repeatedly over a long period of time.

That’s why companies with a genuine brand moat can be excellent long-term holdings.

The key, of course, is not to overpay for the safety that comes with the brand.

I assume you aren’t referring to using substack to build a brand more in lines of companies?